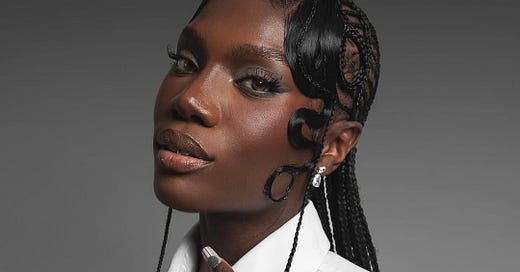

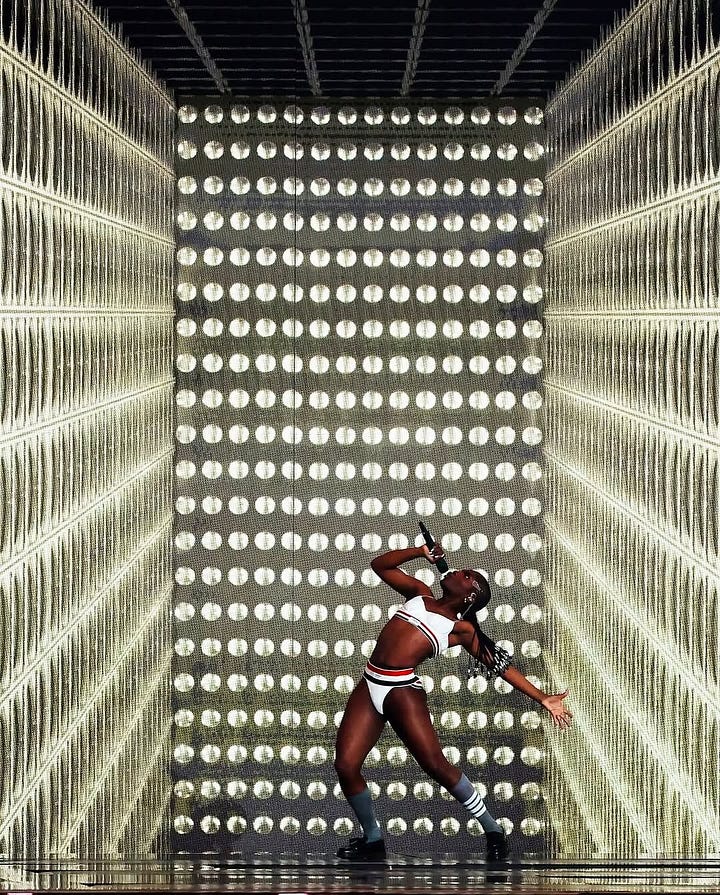

Is Doechii Really an Industry Plant—Or Just Finally Getting Industry Support?

Doechii’s rise is viral, fast-tracked—and raising eyebrows. Of all her peers, why is she the one accused of being an industry plant? Maybe the issue isn’t her.

Despite my best efforts to shut my big mouth, welcome to another post of Confessions of a Pop☆aholic— the only non-safe space for brutally honest pop culture opinions.

As I’m looking for a new main gig, consider Pop☆aholic my new home for now, meaning there will be two to three posts every week. Consider supporting your favorite writer with a subscription— it’s free!

The music industry loves a Cinderella story—especially one it can control. And at first glance, Doechii's rise has all the sparkle: a Grammy win, a viral "freestyle" moment, and a debut that went from underground sleeper to Billboard climber almost overnight. But for fans paying attention, the rollout feels… suspiciously smooth. Despite her undeniable talent and original voice, some have started asking the question no one wants to say too loud: is Doechii the newest industry plant?

This isn't about tearing down an artist—it's about interrogating the machine behind the myth. In an industry that rarely grants women—especially Black women—a frictionless path to success, Doechii's journey feels more like a fast-tracked fairy tale. And that's exactly why it deserves a closer look.

What Is An "Industry Plant"?

But before we go further, let's define the term at the center of this conversation:

An "industry plant" is typically an artist who presents as independent or self-made but is, in reality, heavily backed—sometimes even manufactured—by a label or media machine.

One of the most infamous examples? Milli Vanilli—the late '80s pop duo who skyrocketed to fame with a Grammy win, only to be exposed for lip-syncing songs sung by other vocalists. The backlash destroyed their careers, ending with the Grammy Awards revoking their "Best New Artist" award, thus becoming a cautionary tale about industry fabrication.

In the age of TikTok stardom, the idea of an "industry plant" is more nuanced. Every artist receives some form of behind-the-scenes support. But when a rise feels too frictionless—without the usual industry pushback, missteps, or resistance—it's fair to wonder: how much of it is the artist, and how much is the machine?

The Curious Case of Doechii

In February, Doechii forever cemented her place in the music industry, becoming the third female emcee ever to win the "Best Rap Album" category in the Grammy Awards. My sixth sense started tingling with her post-Grammy win hurrah "Nosebleeds," a freestyle that lost its spontaneous, off-the-cuff magic as it appeared overnight with a Grammy trophy smack on the cover art. Not to mention the plethora of musical coincidences like the "Denial Is A River" hyperventilations and right-hook-named disses fit for a standard cookie-cutter release.

Where the VMAs and AMAs are participation trophies, the Recording Academy's Grammys are the stamp of approval in the music industry. Last year, Gold Derby convinced a recurring voting member to give the publication their ballot for the 2024 ceremony, where discussing "Album of the Year" nominees highlights the bias of members and how notoriety, aka "staying in the spotlight," matters for performers.

Quite frankly none of these nominees are Album of The Year worthy, I found it to be a very weak year for mainstream albums. However, I voted for Midnights. Although I did not enjoy it much compared to Taylor’s previous work, she has been the inescapable face of music so how can I deny her music’s biggest award? I haven’t taken Lana Del Rey seriously as an artist since her infamous SNL performance and never will. Boygenius’ record can be considered decent but I am dissatisfied at how artists like them or Fiona Apple who are making such dull music are seen as the face of rock music, taking spots over actual rock musicians like the Foo Fighters or Springsteen.

via Gold Derby

Doechii’s breakthrough hinged on viral momentum, beginning with 2023’s “What It Is (Black Boy),” bolstered by late-night TV spots and a “Rising Star” honor from Billboard’s Women in Music ceremony in 2023 (followed by their highest recognition: 2025’s “Woman of the Year”).

We [women] are the creatives. We are the execiutives. And we are the innovators who are just as central to this industry as the men.

Doechii accepting the “Woman of the Year” award at Billboard’s Women in Music 2025 [YouTube]

However, what gave her music a thunderous digital pulse was NPR's Tiny Desk Concert, which only premiered in December 2024 and garnered over 14 million YouTube views—outperforming much of her debut mixtape content on the same platform, which received a four-month head start.

Imagine the shock of the music industry when Doechii won "Best Rap Album" for her debut mixtape, Alligator Bites Never Heal, which started at No. 117 on the Billboard 200 albums chart, selling only 11,000 album-equivalent units in its first week. Not only did the Swamp Princess beat out household nominees J. Cole, Future, and Metro Boomin, but 15x Grammy-favorite Eminem, whose decades-long acclaim matches his 281K first-week album-equivalent sales of The Death of Slim Shady (Coup de Grâce).

The Numbers Don’t Lie—But They Do Evolve

While Doechii's album sales remained consistent through Q3 and Q4 of 2024, even doubling at some points, becoming the third female emcee to win the category's 29-year history skyrocketed her sales to 31K units per week, currently peaking at the No. 14 spot on the Billboard 200— a natural post-televised surge and a long way from her No. 117 starting point.

Other female "Best Rap Album" winners have different histories of success and acclaim, which feels incomparable when considering Doechii's win. In fact, some of it is incomparable since Billboard rules and the landscape of music consumption have changed so much that each winner coincidentally reflects such milestone industry moments. It inherently begs the question: Does Doechii's win represent a new era for the music industry, one where they're actually willing to back new talent?

During the paramount of physical consumption, Lauryn Hill's sole, influential album, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, had a first-week sale of 422k copies, spawning three Billboard Hot 100 chart entries, including No.1 hit "Doo Wap (That Thing.)" This success comes after her high-profile exodus from accomplished hip-hop group The Fugees with Prakazrel "Pras" Michel and Wyclef Jean.

When streaming started taking over physical memorabilia, Cardi B's first week sales for Invasion of Privacy saw 255k album-equivalent units, with 105k pure sales. However, these numbers are most likely spiked from the pre-debut album, Billboard monster hits "Bodak Yellow (Money Moves)," Bruno Mars-collaboration "Finesse," the infamous rap beef of "Motorsport, the 21 Savage-featured "Bartier Cardi," and album tease "Be Careful." Other factors influenced her win, including an aggressive media push that disguised Cardi’s undeniable breath of fresh air to finally ice out Nicki Minaj entirely from music forever— scrub her image, chart achievements, and notoriety altogether for a new face— which failed and somewhat reversed.

Welcome To The Label Game

Even if music executives are willing to back new talent, the question remains whether her quick rise equals inorganic, bought success— a question dividing fans and spectators alike. However, what if a label traps you in a success in which your music was never yours? Well, ask Taylor Swift, whose former record label, Big Machine, sold her catalog's masters to Justin Bieber's ex-manager, Scooter Braun, in 2019.

Now, before we dive into more nuance and pop culture examples, I want to make one thing extremely clear: Music labels are loan companies. As a talent representing the company, your job is a) always break even on financial investments with your music career success. And to have unlimited financial backing, you need to b) always generate a greater profitable return than what was initially invested.

However, labels prey on artists with big dreams. While going after poor artists is a no-brainer, they also go after individuals without previous industry experience. This makes it easier for labels to get away with iron-clad contracts that not only ball-and-chain artists to labels and make it (sometimes) impossible to see the fruit of their labor financially or retain artists' music copyrights— which in layman's terms, means an artist's music rights exclusively belong to the label where it was released.

Many artists create independent labels with "Big Three" distribution deals (Universal Music Group, Warner Music Group, and Sony Music Entertainment) to maintain their artistic integrity. Think Megan Thee Stallion, Tinashe, and Kesha.

And if you're not breaking even, you may experience the RAYE treatment of getting zero studio time, zero budget promotion, no "okay" to release music, and being known as the "studio girl" to fill in feature requests. Of course, this was before My 21st Century Blues, Raye's first (independently released) album, despite being previously signed to Polydor for over five years.

However, music copyrighting is largely multifaceted, which is the main industry weakness that Swift exploited… let me explain: While Big Machine retained Swift's master recording rights to previous original work (everything pre-Lover), the "Cruel Summer" singer retained the publishing rights, or copyright to the original composition and lyrics.

Therefore, her re-recordings are considered new creations, not infringements, because she owns the copyright to the compositions and is making new recordings. That is why her Taylor's Versions are slightly different from the original CDs— legally, they must be.

To the music industry, Swift went full-blown Katniss Everdeen à la Catching Fire, re-releasing records with even more success. I can only imagine the emphasis of newer contracts centered around "owning" artists, right down to masters and publishing. Albeit, the jargon watered down with such flowery language that a regular dreamer would first recognize the seven-figure dollar sign before the ill-fated terms.

Is Azealia Banks On To Something?

Twitter's most controversial pop figure, Azealia Banks, quickly pieced together my Doechii hesitations into something coherent. As much as the "212" rapper's unfiltered pop culture takes are cruel for their straightforwardness, she wields an expansive musical and real-life literacy, making her perspectives compelling and objectively not wrong… even when the semantics are choppy.

Caution: Please take a huge grain of salt with Banks' clapbacks because she always had it out for Doechii, even previously calling her a "DEI hire." However, taking away all her microaggressions and stan shade, and that hot-blooded opinion boiled down to how other tenured dark-skinned female rappers (like Asian Doll) could've been put "on" first rather than Doechii. And that's… fair.

This op-ed’s initially thesis started with a quote retweet about killing the "Doechii's rise looks inorganic" narrative, with a fan wagering that perception to the rarity of labels giving "this level of real backing" and "smart, sustained investment" to newer talented artists— today's optimistic take.

However, Banks wasn't ready to let go of Doechii's tight facial tape. When taking a swing at the topic, Banks made sure not to miss noteworthy industry insights, which are true but better decoded using other publicized label-artist mistreatment.

No, it’s because most artists are intelligent enough to not sign those types of deals anymore. The only reason any label has an incentive to invest any kind of money into a mid to whack youtube personality is- a non conventionally attractive dark skinned one at that - 100% signals they’re owning masters, publishing, image rights, rights to the artists name/ getting the lion share of royalties for an insane amount of time in exchange for what to her probably seemed like “life changing money,” but is actually immediate debt. So yeah, they found a broke girl in the trenches that they could pay a small sum to push product they had sitting around with the writers they have signed up for pub. We just saw this happen with Cardi B lol. Nice try tho.

No notes—Banks isn’t wrong here. Her critique, if anything, cracks open a bigger truth: most artists, regardless of their size or status, operate with far less creative control than corporate-run labels wants us to believe. And, in terms of race, the numbers back her up.

Black women in the music industry are paid 25% less than White women and 52% less than White men.

Just 19% of Black women earn 100% of their income from music in comparison to 40% of White women which earn 100% of their income.

73% have experienced direct or indirect racism—and 80% have encountered racial microaggressions.

57% of Black music creators say they’ve seen white contemporaries promoted ahead of them, despite being more qualified.

And among Black women, 43% have felt pressured to change their appearance due to their race or ethnicity.

Though the data is UK-based, the implications are hard to ignore—especially in a U.S. industry where Black creators make up an even larger share of the talent pool. If this is how it looks in a country where Black people account for roughly 3% of the population, what should we infer about a nation where 31% of the music industry is Black?

Pop Stars v. The Fine Print of Success

A seven-figure record deal might sound like a dream come true—until you realize how often that dream ends in debt, silence, or erasure. In the music industry, success on the surface rarely reflects the reality behind the scenes. From label control over releases to recoupable costs that strip away profits, artists—especially Black women—often find themselves navigating fame without financial or creative freedom.

I’ve done everything they asked me, I switched genres, I worked 7 days a week, ask anyone in the music game, they know. I’m done being a polite pop star. I want to make my album now, please that is all I want.

Source: RAYE (@raye) on Twitter/X [2021]

We've seen this play out time and time again: artists at the top of their game, only to be sidelined, silenced, or buried in bad contracts. And sometimes, it’s not just about money—it’s about power, protection, and whose careers are allowed to thrive after controversy.

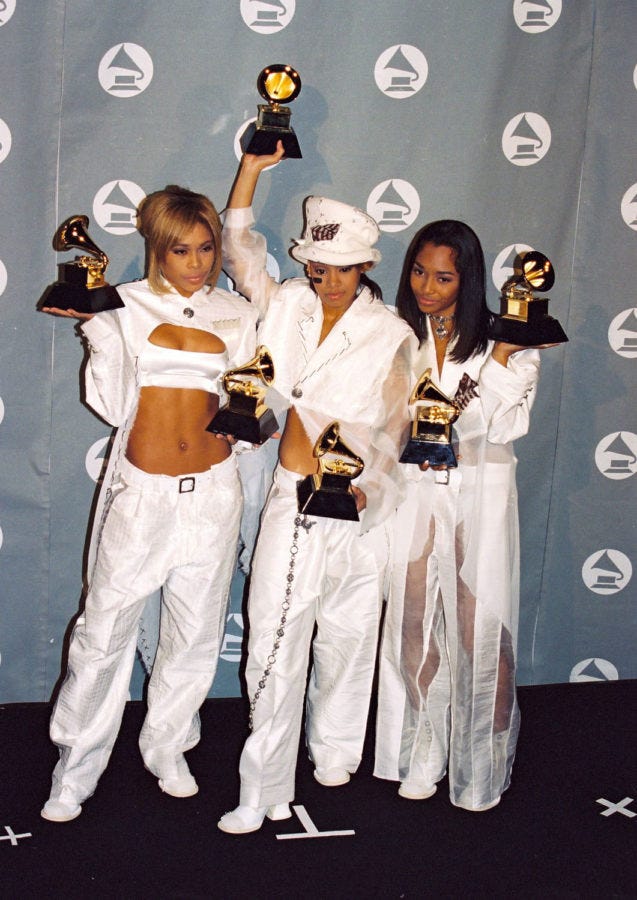

TLC v. Pebbitone & LaFace

In multi-million-dollar label deals, everything goes back into the music— tour stages, booking agencies, music videos, press, managers, bandmates, social media, radio play/streaming, and even awards. However, what happens when you're at the pinnacle of your success and broke? Just ask the best-selling R&B girl group, TLC.

When they took home two Grammy awards in 1996 off the back of their RIAA-certified diamond-selling album CazySexyCool, fans were shocked to learn TLC filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy the year before. TLC said that they had debts totaling $3.5 million, some of it due to Lopes's insurance payments arising from the arson incident and Watkins's medical bills, but the primary reason being that the group received a non-industry standard deal from La Face Records / Pebbitone Inc. which they were renegotiated and owned the TLC name by 1999's (also RIAA-certified diamond-selling album) Fanmail.

We are the biggest-selling female group ever. 10 million albums worldwide. We have worked very hard. We have been in this business for five years. Five years, and we are broke as broke can be. […] You can sell 10 million albums and be broke if you have greedy people behind you. […] Everybody's looking at the videos, they're looking at the success of the album. So they're thinking that you're on top of the world. And you know, when you're quiet like that, no one knows. So that's why we're telling it.

Source: TLC's 1996 Interview After Performing At The Grammy Awards [YouTube]

According to the members of TLC, ironically, the more successful the album became, the more debt they were in. Not only were the girls three-way splitting 56 cents per album sold, Arista Records, LaFace, and Pebbitone recouped their investment for recording costs and manufacturing and distribution (standard recoupable charges in most record contracts), both Pebbitone and LaFace Records went on to charge for expenses such as airline travel, hotels, promotion, music videos, food, clothing, and other expenses. In addition, managers, lawyers, producers, and taxes had to be paid, leaving each group member with less than $50,000 a year after having sold millions upon millions of albums.

In promotion for Legends of Rock's 1996 show, "Pretty Thing" singer Bo Diddley spoke about how 1950s-style of poor contracts were making a comeback then. Perhaps the most notable references Diddley referred to were how Little Richard received only a small payment for the rights to "Tutti Frutti," and how Neil Young purposefully made uncommercial albums to get out of a contract.

Janet Jackson v. Nipplegate

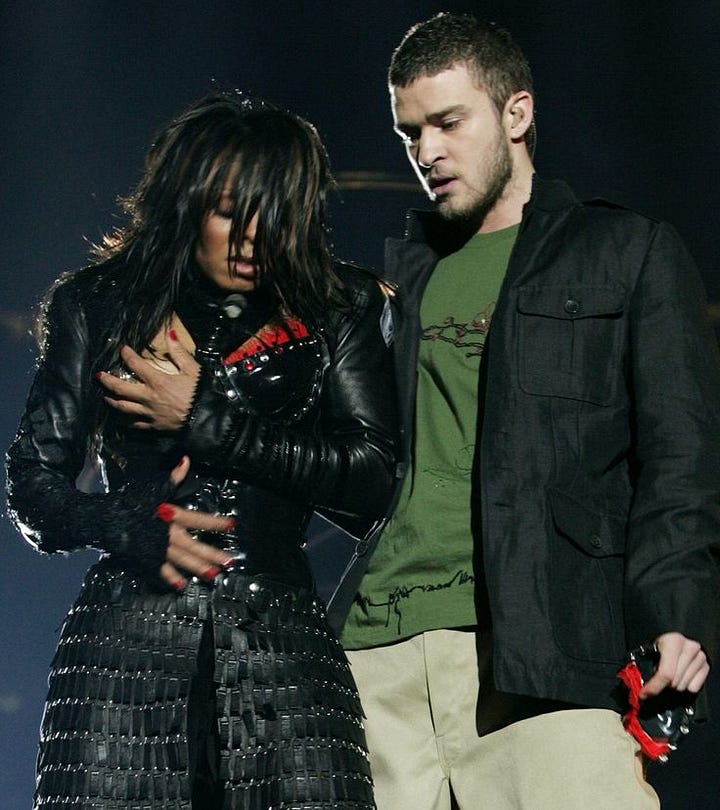

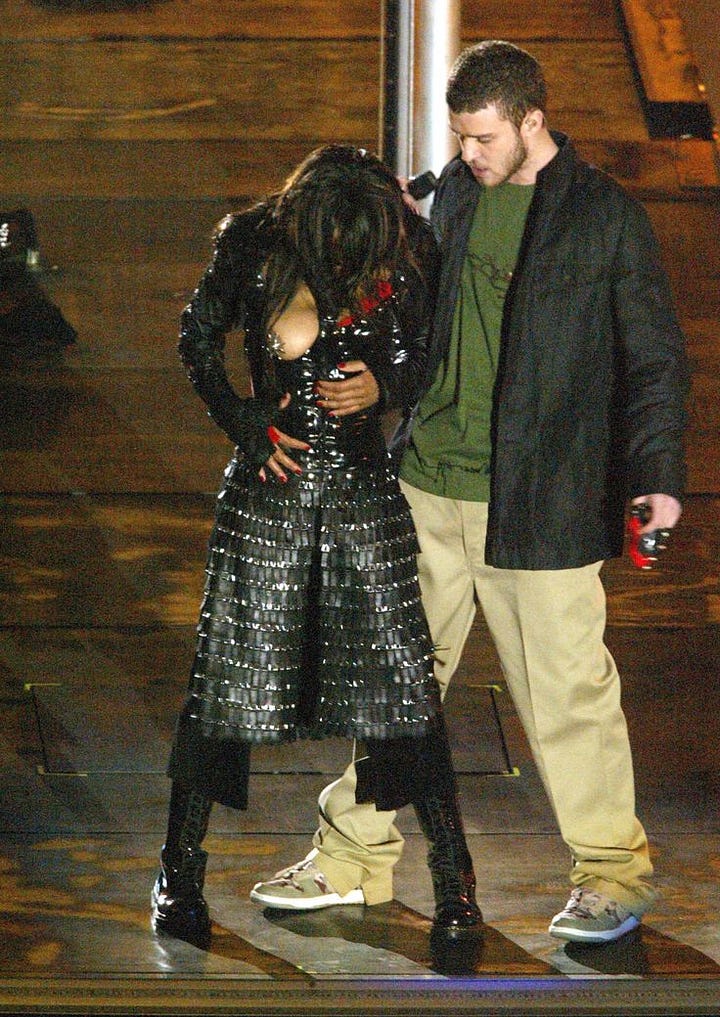

The music industry has a long history of punishing Black women for controversies they didn’t create—and Janet Jackson remains one of its most blatant examples. After the infamous 2004 Super Bowl halftime show, where Justin Timberlake accidentally exposed her breast during their final pose, the media frenzy was instant, including over 500K FCC complaints.

While Timberlake brushed it off as a "wardrobe malfunction," Jackson became the scapegoat. She issued multiple apologies, pulled out of the Grammy Awards under CBS pressure, and was subsequently blacklisted across Viacom-owned platforms—MTV, VH1, and CBS Radio among them.

2004’s Damita Jo debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard 200, with 660K copies sold, marking her sixth consecutive multi-platinum album; however, it saw a dramatic decline in radio play and promotion due to her industry-wide blackball.

Many ask, Well, you can’t just erase an icon, right? No, but Virgin Music (cough Sony Music) tried. Her next two albums—20 Y.O. (2006) and Discipline (2008)— faced the same fate of underperforming, each selling fewer than 600K copies in the U.S. this time, despite top-tier production.

Meanwhile, Timberlake faced zero repercussions. Just days after the incident, he performed at the 2004 Grammys and went on to drop 2006’s iconic FutureSex/LoveSounds, solidifying his reign as a solo pop juggernaut with three Billboard No. 1s.

All the emphasis was put on me– not on Justin.

Janet Jackson on The Oprah Winfrey Show 2006 [YouTube]

It wasn’t until 2021—seventeen years later, and only after public backlash following Framing Britney Spears—that Timberlake offered a public apology via Instagram. Jackson, however, never received the same redemptive media arc.

Her trailblazing legacy remains iconic , but her career trajectory post-2004 serves as a sharp reminder: in the music industry, forgiveness is often selective, and success after scandal is a luxury rarely afforded to Black women.

Jojo v. Blackground Music

When R&B-pop singer Jojo signed to Blackground Music, she admitted to Vulture, "I was 12 when I got into my contract; my mom signed it for me and didn't have any experience in the industry." However, a year after signing, her trip to stardom got the stamp of approval, becoming the youngest solo artist in Billboard history to score a No. 1 hit with 2004's "Leave (Get Out)," at age 13.

Although Blackground's claim to fame was singing the late Aaliyah, its notoriety ended there. Horror stories emerged about poor internal management, with Jojo A&R quietly vanishing from the label. Soon, as Blackground burned through "Big Three" distribution deals, there was such internal instability that teenage Jojo couldn't release music nor get out of her seven-album contract deal for over a decade.

At the time of Vulture's article, Jojo was 24.

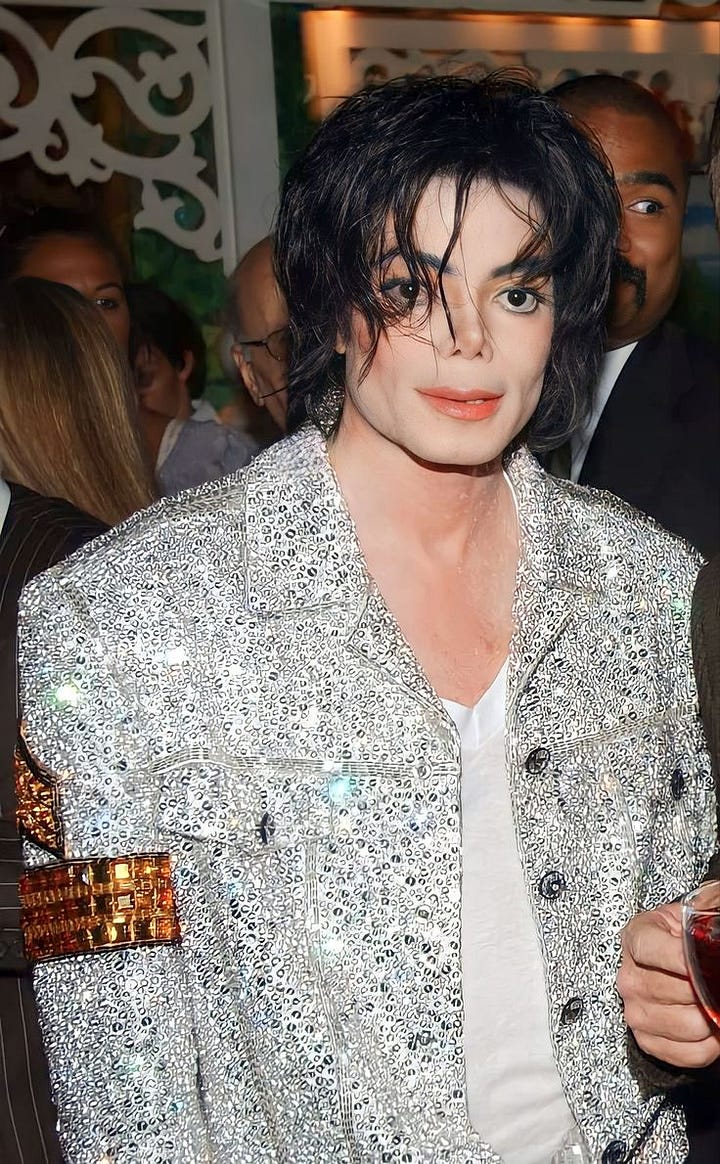

Michael Jackson v. Sony Music

Michael Jackson's fallout with Sony Music is one of the most infamous artist-label feuds in music history— partly as a reminder of Jackson's star power as it's still massively uncommon for artists to openly speak badly about their record label as Michael did, usually fearing retaliation.

After the massive success of Thriller, Jackson re-signed with Sony Music in 1991, but with heavier conditions: he had to release at least three studio albums, one remix album, two more greatest hits collections, and a compilation box set.

By 2001, with Invincible completed, Jackson sought to exit his contract early to regain creative and financial control. Sony retaliated by cutting promotion altogether, canceling singles, and shelving the 9/11 charity song "What More Can I Give." Jackson later accused Sony's then-president Tommy Mottola of being a "racist and a mobster," which destroyed any chance at a contract renewal despite Invincible selling 13 million copies. In fact, Sony penalized Jackson $25M for not touring in U.S. territory and forced the greatest hits release of Number Ones, citing the company's distribution rights with the King of Pop’s catalog.

In Jackson's controversial death, Sony bought the exploitation rights of Jackson's catalog to maintain distribution rights past 2015, including the already-released albums Michael in 2010 and Xscape in 2014. (It doesn't take a mathematician to realize Sony was scare of losing MJ's royalty checks.)

However, Michael stirred controversy: three songs were allegedly fake (originally performed by Jason Malachi), and Jackson's family and collaborators heavily criticized the unauthorized release.

Despite wanting independence, Jackson remained tied to Sony—even in death—as they profited from his legacy. Let this be a music industry lesson: when money talks, who needs people?

Is Top Dawg Entertainment Doechii’s Fairy Godmother?

How does this all fold back into Doechii? Well, it doesn't. Doechii, for better or worse, is on top of the world— and if there's a problem, as we've dissected, nobody would know until it becomes a news headline.

However, I think Banks' main critique of Doechii is that the Swamp Princess is falling into Black stereotypical molds that are cringe, aesthetically or sonically, calling her post-YouTube days material as "this new Crooklyn the musical shit" and "some corny Issa Rae playlist black girl magic algorithm"—something that Doechii's label, Top Dog entertainment, "deserves the greater credit" for as "there was no time to develop" Doechii., emphasizing that the Floridian is merely the product of the record label's already existing talent pool.

However, Doechii has been with the specialized American independent record label for hip-hop and R&B artists since 2022, becoming the label's first female rapper.

As much as Banks clowns Doechii for being a product of TDE— mainly writing and image credits— that's kinda the point. To use Banks' words, a label's job is to develop their artist. Whether it's authentic to Doechii is a moot point since I doubt the Swamp Princess has any creative leverage after just securing her first Grammy and mainstream notoriety three years post-signage.

However, Banks isn't wrong: it takes a label to create a name. Every label enlists songwriters, producers, sound engineers, artist development, publicists, social media, marketing, tour, and plenty of other teams to help make icons like Madonna and Lady Gaga effortlessly cool, just like newer stars like Tate McRae and Benson Boone. Artists are a product that fans buy into, and that's thanks to labels, again for better or worse.

Kendrick Lamar, TDE’s former flagship artist, has consistently spoken positively about the label, recalling In a Billboard interview, "It's crazy - we actually imagined this moment together in that little studio years ago, and now that day is here," referring to his success with TDE.

However, his friend and fellow A-list signee SZA has frequently voiced her frustrations with the label. Through social media, she has openly addressed her strained relationship with TDE president and former manager Terrence "Punch" Henderson, who was allegedly responsible for delaying the release of her Grammy-winning sophomore album S.O.S. In a now-deleted Twitter/X post, she even referred to their working relationship as "been hostile."

While TDE concentrates on verbatim "artist management, publishing, and merchandising," it contracts "Big Three" record companies for distribution ventures—a fairly regular practice. Doechii got a sweet joint venture with Capitol Records, where ex-alleged "industry plant" Ice Spice resides.

However, how are we excluding Boone from the "industry plant" chatter? Did we forget that in 2021, the "Beautiful Things" singer left American Idol after making the Top 24 and miraculously got signed under WMG (by Imagine Dragons frontman Dan Reynolds) that same year? Many individuals chalked up his early online presence and TikTok fame to his monster breakout hit "Beautiful Things," which has now accumulated over 2 billion streams on Spotify.

However, why aren't the same conversations allowed for black and female artists like Doechii or Ice Spice, who were conveniently accused of using Streaming Farms to peddle breakout hits like "ANXIETY" and "Think U The Shit (Fart)" despite having insane pre-release success, including six-digit TikTok creates using the sounds individually?

**For clarity, Doechii first uploaded the Gotye-sampled "Anxiety" to YouTube in 2019 with 200K views. This number significantly increased to an astonishing 3,000,000 views upon its official release in 2025, all starting from a TikTok sound, which had over 80K mentions within 24 hours and 650K by the end of the weekend, according to VIBE.com.**

So… What Is an Industry Plant in 2025?

By now, the term industry plant feels more foggy than final—less of a smoking gun, more of a smoke machine. Sure, there are still Milli Vanillis out there—acts built for the spotlight with a team behind the curtain and a script in hand.

But in today’s landscape, where AI-generated songs, algorithmic appeal, and TikTok virality reign, the question has shifted from if someone’s manufactured to how intentionally their image is built—and why some artists are allowed a seamless ascent while others aren’t.

Even the Recording Academy is adjusting, adding new Grammy categories and drawing ethical lines around artificial intelligence in music. Meanwhile, Gen Z listeners are pivoting from traditional radio spins and retail sales toward digital moments—bites, visuals, vibes. In this new media economy, artists are brands, and “authenticity” is often the product of marketing finesse.

So maybe the question isn’t whether Doechii is an industry plant. Maybe it’s: why are some artists allowed to benefit from machine-made momentum, while others get called out for it?

Doechii’s Grammy win places her in a growing lineage of female rappers who cracked the glass ceiling—but her rollout feels different. It feels… newer. Does Doechii rise point to a shift in how the industry rewards artists? A model where virality trumps longevity, or branding outranks bars?

Just look at this year’s “Best New Artist” winner, Chappell Roan. She’s been working in the music industry for almost a decade, quietly building her “Pink Pony Club” catalog while navigating label politics and personal setbacks. It wasn’t until a perfect storm of viral momentum—starting at last year’s Coachella—combined with her aesthetic identity and fan-led hype, that the industry caught up to her. Suddenly, five-year-old singles were topping the Billboard charts. It’s not that Chappell wasn’t ready—it’s that the story hadn’t been packaged just right.

We don’t need to tear Doechii down to question the system that lifted her up. But if we’re going to crown new pop royalty, we should at least acknowledge who gets the Cinderella story—and who gets cast as Joan of Arc. In today’s industry, some artists are praised for a polished, well-funded rise, while others, often women and people of color, are dragged for the same thing. The difference isn’t who’s getting help—it’s who’s allowed to succeed without being punished for it.

If you made it this far—congrats! You just witnessed the anatomy of an artist who refuses to be boxed in, buffed out, or branded too early. Now, let’s take a post reading quiz:

🌱 Do you think Doechii is an industry plant?

💬 Why are we quick to label artists “industry plants” instead of celebrating early-on success?

💥 Which infamous artist-label dispute did I miss from my pop culture examples?

Drop your thoughts below. Or don’t. Either way, I will be streaming my favorite Doechii song, “Crazy,” all day!

And if this post served, do me a favor—share it! Let’s spread the gospel of Pop☆aholic by gifting your fashion-obsessed friend a subscription!

Follow me on social media at your own risk (i.e., an unbelievable amount of Instagram story drivel). While I preview my work there, you can always read the full thing right here!

Bye for now, xo.